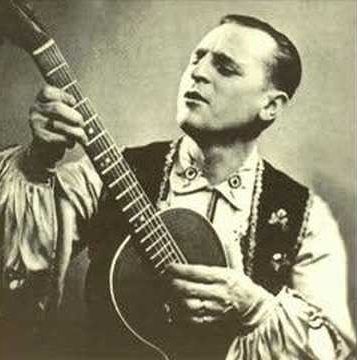

On the bone records that survive, the most of music is Russian. Some of it could be called Soviet jazz or jazz-influenced but a great deal could not. Much of it was the repertoire of émigré artists like Pyotr Leshchenko, a singer who might be described as 'the star of the Bone underground', as his music features on x-ray records more than any other artist. Listening to it now, the haunting, romantic melodies, old-fashioned rhythms and sometimes dramatic, sometimes innocuous lyrics don’t seem ‘anti–Soviet’. So why would it have been forbidden?

There were two reasons: firstly Leshchenko was a traitor as far as the Soviet regime were concerned because he was considered to be a ‘White’ Russian émigré of noble blood. In fact he was born into a Ukrainian peasant family but by living in the West he was tarnished by association with the capitalist oppressor, and by not returning to the Motherland to help the Great March Forward, he effectively set himself beyond the pale. Secondly, he performed in styles which had increasingly became prohibited as Stalin increased the cultural stranglehold after the Second World War: the ‘gypsy’ romances and flamboyant tangos he performed with exaggerated gestures and passionate changes of tempo which were condemned as being superficial and encouraging the wrong sort of passions in young Soviet minds.

Like the life of singer Vadim Kozin, Leshchenko’s story was a cold war era musical tragedy, But Kozin was a Soviet citizen, beloved not only of the Russian people but, for many years, of the establishment. The charges of homosexuality and moral corruption on which he was arrested, convicted and sent to the gulag were just an excuse to bring him down. His extravagant lifestyle, increasing celebrity and wealth inevitably made him a target as the prurient personality cult of Stalin developed. Leschenko's life - and death - were quite different.

A musical child, Pyotr's star rose from poor beginnings and local performances through foreign travel and international theatrical shows until he was so popular that he became known as ‘The King of Russian Tango’. As his fame increased, he performed for the European nobility and Russian aristocratic émigrés in his own cabaret in Bucharest - a venue described as an Eastern version of the famous Parisian 'Maxim’s'. But, like many émigrés, he nurtured a yearning to return to his homeland. During the Second World War, he had the opportunity to do so when the Romanian army occupied Odessa. His concert performances there were hugely oversubscribed and became legendary, increasing his fame in the motherland even more. In the subsequent occupation of Romania by the Soviets, life could have taken a vengeful turn for the worse, but he seems to have been protected by General Burenin, the commander of the Red Army in Bucharest who was a secret admirer of his music.

But fatally, Leschenko seemed to have come to believe that such patronage extended to other figures in the Soviet establishment and he could risk making an application that he and his wife Vera be allowed to return to the Soviet Union. In 1951, a week after official permission was granted, they were arrested. He was sent to a prison camp in Romania while Russian-born Vera was extradited and condemned to hard labour camp in the Soviet Union for ‘marrying a foreigner’. As for Kozin, their tragedy was almost of Greek proportions - the fall from fame, success, opulence and adoration must have been almost impossible to bear in the indiscriminate brutality of person life. In a final poignant twist to their tale, they both outlived Stalin and might have been reunited but Vera on release, believed Pyotr dead and stayed in Russia,.*

He died forgotten and alone in the camp without them meeting again.

Like Kozin’s repertoire, Leschenko’s music had become immensely well-loved during earlier, more permissive Soviet times, which is why after the war, he featured on many of the x-ray records copied from smuggled 78s or cut from foreign radio broadcasts. Apparently, when his records were played, people would fall silent. Bootlegger Rudy Fuchs says that this was because his mysterious, other-worldly voice awoke romantic thoughts of an imagined, happy elsewhere in listeners. Plus, nobody in the Soviet Union really knew much about his actual life and so he attained a kind of mythical status.

He was so popular that a Moscow baritone, Nikolai Markov, who had a very beautiful and similarly tender voice, was hired to record forty songs of his repertoire. These were copied onto x-ray and successfully passed off as being by Leschenko himself. One, ‘The Cranes’, considered the quintessential Leshchenko tune amongst Bone buyers, was in fact never recorded by the master himself.

*Vera Leschenko died on December 18, 2009, age 86.